How do we switch between two languages?

Article by Elissa. Originally posted on ‘The Language Brain’. Reposted with permission.

How do our brains manage two different languages, and how do they control them? We take a look at a bit of the science behind bilingualism.

First of all, what is bilingualism?

Generally speaking, bilingualism is the “fluency in or use of two languages”. The definition of “fluency” can be a thorny issue, and something I won’t go into here (it deserves its own post), but for this article: bilinguals are people who can communicate effectively in two languages, even if they’re not “native-like” in fluency.

More than 50% of the global population is said to be bilingual, and in some places, speaking three or more languages is considered common. If you speak three languages you’re “trilingual” (tri- = three), more than that and you are “multilingual” (multi- = many) or a “polyglot” (poly- = many; glot coming from “tongue,” i.e. “many-tongues”. Ew.). In many parts of the world, monolingualism, or knowing only one language (mono- = one), is actually quite uncommon.

Fun Fact: Bimodal bilingualsare bilinguals who know a signed language and a spoken language, such as Auslan (Australian Sign Language) and English. As we saw, bi- = two, and modal = mode or form. This would make spoken bilinguals unimodal bilinguals (uni- = one, like in unicorn).

Types of bilinguals

Every bilingual brain is unique, even if they speak the same two languages. There are many factors that influence how the brain develops and organises two languages in one mind:

- how old you were when you started learning a language

- how much you’ve heard/read/written/spoken a language

- how motivated you are to use a language

- how you learned a language (e.g. at school, home)

- how similar the languages are

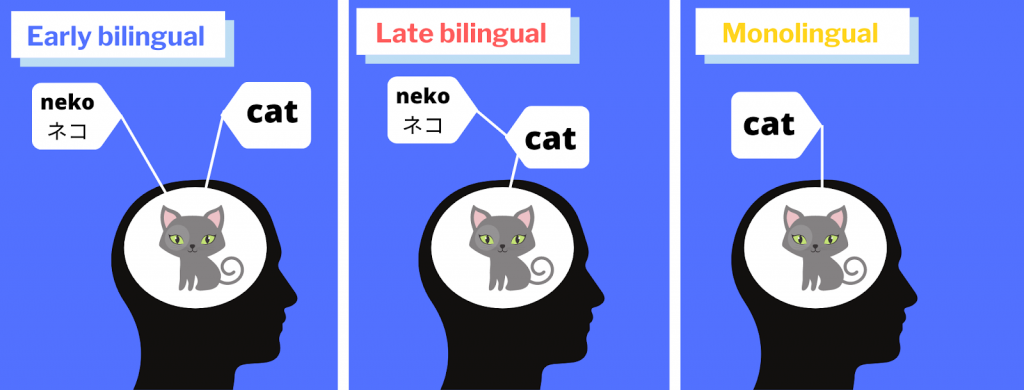

How old you were when you started learning (also known as age of acquisition) is particularly influential. It can even alter the structure of the brain. Because of this, bilinguals are often divided into two types: early bilinguals – those who learned two languages from early childhood – and late bilinguals – those who start learning a second language later on, usually as a teenager or adult.

Early v Late Bilinguals

At first, early bilinguals seem to have an advantage over late bilinguals. Young children acquire language much faster than adults, whether it is one language or two (or three). This seemingly magic ability tends to disappear towards puberty though, marking an end to what is known as the critical period for language learning.

Another advantage is that typically early bilinguals have been exposed to the language for longer, and often from birth. Babies start tuning into the sounds of their native language(s) even before they are born. When they are born, they can distinguish between all human language sounds, but by around 10-12 months, they start to tune out the sounds that aren’t used in their language. For example, while English-learning toddlers can hear the difference between “l” and “r” as it is used in English, toddlers raised speaking only Japanese (where the “l” and “r” sounds are not differentiated) do not.

So our baby brains listen to the language sounds around us, and eventually decide not to pay attention to the sounds we don’t use. As an adult, learning new sounds and pronunciations can be very challenging – perhaps because your brain learned to ignore them many years ago!

In the past, people thought learning two languages was bad for children; that it would confuse them. Fortunately, such myths have since been busted. For example, while it is true that bilingual children often start off a bit slower with vocabulary (in each individual language), they catch up by around the age of five.

Early bilingual children are also more flexible in learning new patterns and vocabulary. As they grow up learning that everything can have two different names – one in each language – bilingual toddlers show more flexibility than monolinguals in learning new words for known objects.

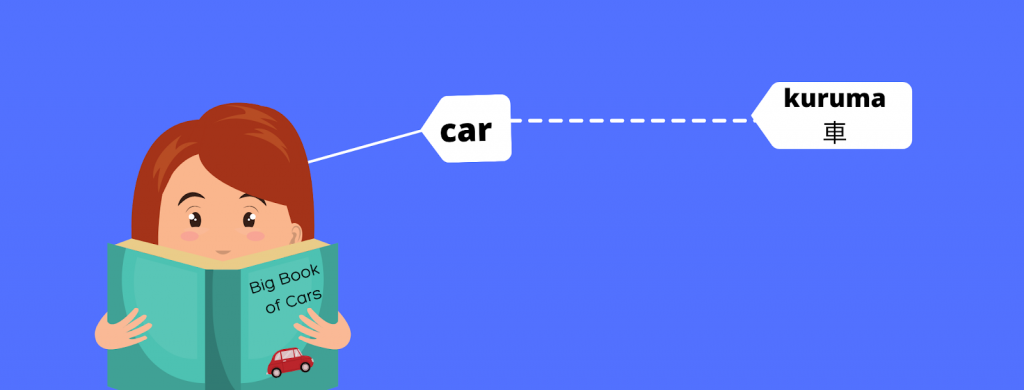

Late bilinguals learn vocabulary from their second language a bit differently. As they already have a word, they tend to translate a second language through their native language (as we saw in the last post). This can be helpful, as they already know the concept, but it can also take a lot of time and effort.

But the brain can learn, change and grow! And does so over our entire lifetime. Depending on how much they hear, see and use the language, late bilinguals can become just as proficient as early bilinguals; they just use a different path.

Fun Fact Another kind of bilingual is the passive or receptive bilingual: someone who understands a second language but does not speak it. This is not uncommon in migrant families. One example is a Spanish-speaking family who has moved to the USA. The parents learn to understand the language of their new country, but do not speak it. They can understand their children (who speak English) but will speak to them only in their native language (Spanish). Likewise, the children may also be passive bilinguals. They understand Spanish, but as they live and learn mostly in English, they do not speak it.

How do bilinguals switch between languages?

Have you ever been on a plane and marvelled at the way the flight attendants nimbly swap languages for different passengers? Or wondered how that memorable Melbourne Auslan interpreter translates COVID news so quickly on the spot? Or maybe you’re wondering how your own bilingual brain works. Well, though it may appear easy from the outside, there is a lot going on in the brain when a bilingual switches languages.

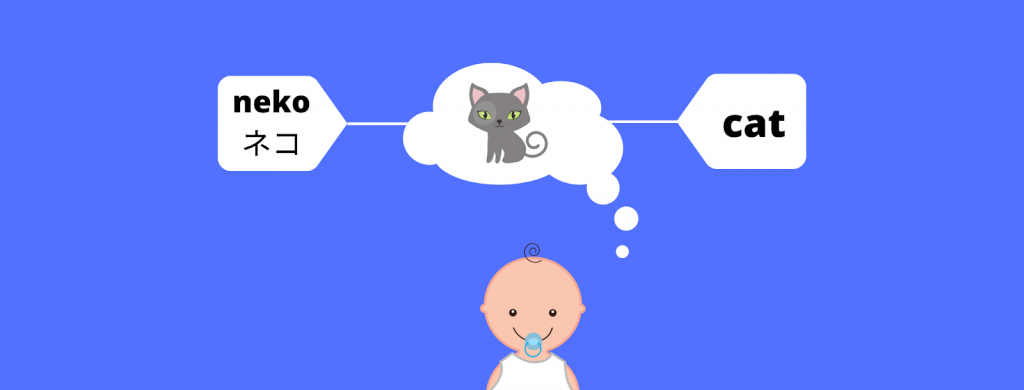

Essentially, bilinguals have both languages active at the same time. Even when using one language, their brain activates the other language too; this is known as parallel activation. So if you speak Japanese and English, when you hear or read the word “car,” your brain activates the word “kuruma” (車) as well, even though you’re not aware of it.

Bilinguals just need to select the language they want. Easy, right? Not always. In a bilingual brain, both languages are competing to be chosen. Kind of like having two Hermiones in your head, both dying to answer the question.

Language Control

To choose the right language, bilinguals need to inhibit – that is, suppress or push away – the language they don’t want to use. They need to tell that other Hermione to ssshhhhh! And this requires effort.

Inhibiting a language also means that it is harder to “re-activate” it later – something language researchers call switching cost. For bilinguals (or language learners) it might feel like this: you’re hanging with friends from your language class, deep in conversation in your second language and feeling great about how well you’re doing, when suddenly, someone asks you for a word in your native language. You pause, blanking: …what is the word again? As you’ve inhibited your native language in order to speak your second language, it will take more time and effort to reactivate it.

A lot of this depends on which language is stronger or more dominant. There is such a thing as a balanced bilingual – someone who is equally good at both languages – but for many people, one language is usually dominant, meaning they are better at it and/or use it more often. The more dominant language needs more inhibition than the weaker language.

It’s not all hard work!

While it’s true that language switching can be costly, recent research is finding that some things make language switching easier.

1. Be equally strong

If your knowledge and use of both languages is equally good and you use them pretty much equally every day – as professional interpreters do – it seems that switching costs are low. So make sure you’re using both of your languages regularly.

2. Code-switching

When bilinguals get together, they often code-switch, meaning they switch between languages very quickly – often within the same sentence. It’s even become common in pop music, from Korea to the Americas. Code-switching used to be discouraged, but it is actually a very normal part of the bilingual experience, and research has shown there may be little to no switching cost when it happens.

Follow this link for an awesome video example of code switching at work.

3. Who are you talking to?

Research has found that our knowledge of our listener and what language they speak can help activate a language even before a word is spoken. That is, if you know someone only speaks English, when you see them, you activate your “English mode” in preparation.

4. Where are you?

Similarly to people, we often associate places with particular languages e.g home, school, work, the market. So being somewhere may prepare you to speak a certain language, which can make it feel easier to use. For example, if you only speak English at school, it may feel strange to suddenly start speaking your other language.

5. If it sounds right

Every language has its own unique selection of sounds. Scientists at the University of Arizona found that when Spanish-English bilinguals hear the sounds of one language, e.g. English, their brains switch to “English-mode” and start to predict English. Likewise, if they hear the sounds of Spanish, they switch to “Spanish-mode” and start to predict Spanish. The mode you’re in even changes how you hear a word!

6. If it’s voluntary

Within bilingual communities, people generally choose when they want to switch a language. Recent studies conducted in Europe and the UAE suggest that outside the lab, in these more natural contexts, switching between languages is easier when it’s voluntary.

Final words

There are many different kinds of bilinguals, and the world is full of them. Switching between languages can take effort, but it is also a completely normal part of #bilinguallife . Stay tuned for more brain facts for mono-, bi-, and multilinguals. In the next post we’ll discuss why we sometimes forget words – even in our native language!